The British Library – A lesson in Incident Response

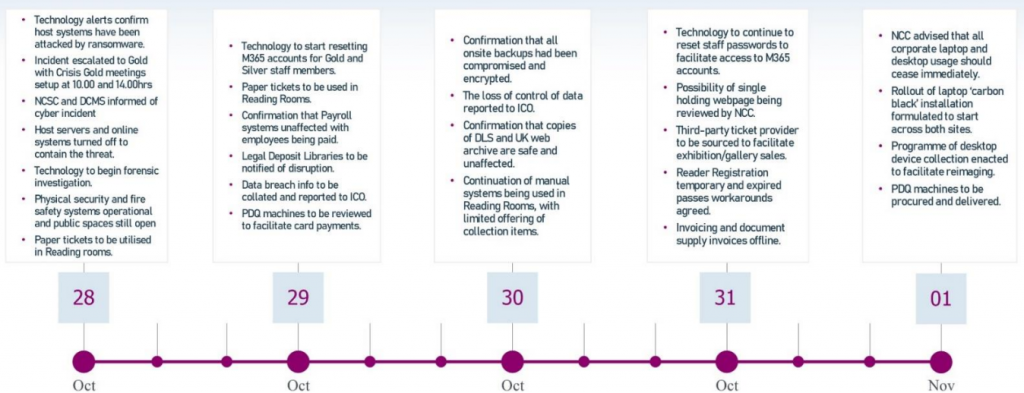

Saturday the 28th October 2023 was a very dark day for The British Library – it was a day that they are still trying to fully recover from, it was the day they found out they had been compromised by the Rhysida ransomware gang.

On the 8th March 2024, the British Library published a fairly comprehensive report into that incident, one which covers the initial response, the subsequent fallout, and the long road to recovery. A report that is fairly unusual in this space that exposes the failings of the Library, but ultimately leads to a set of lessons learned that the Library, and others can use to ensure an attack of this nature does not happen again, or if it does, has minimal impact.

Key findings

The 18 page document released by the British Library provides a timeline of the events in October 2023 and outlines the plans for the future operations of the vital archival and research institution.

The 1st signs of the attack came at 07:35 on 28 October 2023 when a member of the library’s technology team was unable to access the library’s network.

Initial escalation and investigation of the incident within the team was conducted inline with the Technology Major Incident Management Plan which confirmed the likelihood that the incident was the result of a cyber-attack.

At 09:15 the library’s Crisis Management Plan was invoked by the Business Continuity Manager and the Accounting Officer, and Chief Officers were contacted and informed of the incident by 09:21 and the Gold Crisis Response Team were subsequently notified.

After consultation with the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), specialist cyber security advisers NCC Group were procured immediately to support the Library in managing its response process.

NCSC attended a subsequent Gold meeting at 14.00 on 28 October and provided early advice on incident handling, including communications strategy.

Threat Hunting

Forensic investigations and analysis of records indicates the strong likelihood that the criminal actors initially gained access at least three days before the incident became known to the library staff.

Evidence of an external presence on the library network was identified at 23:29 on Wednesday 25 October 2023,with the first evidence of movement around the network at 23:32.

The first detected unauthorised access to the network was identified on a Terminal Services server. This server had been installed in February 2020 to facilitate access for trusted external partners and internal IT administrators, as a replacement for a previous remote access system. As with many other organisations, remote usage had expanded during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In common with other on-premise servers, this terminal server was protected by security controls such as firewalls and anti-virus software, but access was not subject to Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA).

MFA was introduced across the Library in 2020 to increase protection of all remote activities relating to cloud applications such as email, Teams and Word, but for reasons of practicality, cost and impact on ongoing library programmes, it was decided at this time that connectivity to the British Library domain (including machine log-on access and access to on-premise servers) would be out of scope for MFA

implementation, pending further renewal of the Library’s infrastructure.

It is considered likely that the absence of MFA contributed to the attackers’ ability to enter the system via this route.

In the early hours of the 26th October 2023 (01:15), the library’s IT Security Manager was alerted to possible malicious activity on the Library network from the library’s IPS (Intrusion Prevention System) which had automatically blocked the suspect activity at 00:21.

The IT Security Manager extended the automatic block beyond the pre-set expiry, undertook a vulnerability scan (which came back with no results) and actively monitored activity log. No repeat activity was seen.

The incident was the escalated to the IT Infrastructure team at 07:00 where further investigation including

detailed analysis of activity logs, did not identify any obviously malicious activity and they subsequently performed a password reset before unblocking the account later that day.

In hindsight, the library and its advisors believe this initial intrusion to have been hostile reconnaissance of the network, as a precursor to the eventual attack.

Network complexity

The British Library has historically had an unusually diverse and complex technology estate, with a

large number of legacy systems formed out of the very different collections and organisational cultures brought together by the 1972 British Library Act, along with the periodic subsequent addition

of other collections and organisations (most recently Public Lending Right in 2013).

The Library collects and preserves websites, ebooks and ejournals under legal deposit; and hosts the catalogue of the national collection, administers the Public Lending Right, digitises millions of heritage items as well as sound and video recordings.

As well as the above, it has a commercial online and onsite shop, box office, Reader Registration system and a multitude of back office support systems, as well as an extensive security and door access network.

The library also has digitisation partnerships with, among others, the Qatar Foundation, Find My Past, National Life Stories, the Endangered Archives Programme and the International Dunhuang Programme.

The complexity of the library’s IT estate was increased significantly in 2013 by the implementation of the Non Print Legal Deposit Regulations, in partnership with the other five Legal Deposit libraries of the UK and Ireland. This has had an impact on the library’s ability to remain compliant with developing security standards.

Accreditation to Cyber Essentials Plus was successfully achieved in 2019, but changes to

the standard in 2022 meant that the library ceased to be compliant pending replacement of some of the

older core systems. Work to address this, including a major programme approved by the British

Library Board in 2022 to procure and implement a new library services platform, was under way at

the time of the attack.

From the investigation into the incident, it is firmly believed that the particular nature of the infrastructure contributed to the severity of the impact of the attack, in three specific ways:

- The historically complex network topology allowed the attackers wider access to the network than would have been possible in a more modern network design, allowing them to compromise more systems and services

- Some of the older applications rely substantially on manual extract, transform and load (ETL) processes to pass data from one system to another. This substantially increases the volume of customer and staff data in transit on the network, which in a modern data management and reporting infrastructure would be encapsulated in secure, automated end-to-end workflows

- The reliance on legacy infrastructure is the primary contributor to the length of time that the library will require to recover from the attack. These legacy systems will in many cases need to be migrated to new versions, substantially modified, or even rebuilt from the ground up, either because they are unsupported and therefore cannot be repurchased or restored, or because they simply will not operate on modern servers or with modern security controls.

Data exfil

Jisc, who provide the Library’s internet access and monitor movement of data across their networks, identified that an unusually high volume of data traffic (440GB) had left the library’s estate at 01.30 on the 28th October. In total, over 600GB of data was stolen by the criminal gang.

First, a targeted attack copied records belonging to the library’s Finance, Technology, and People teams, resulting in the copying of entire sections of the library’s network drives. These files represented around 60% of the content copied in the attack.

Secondly, a keyword attack scanned the network for any file or folder that used certain sensitive

keywords in its naming convention, such as ‘passport’ or ‘confidential’, and copied files from

corporate network systems as well as from drives used by staff for personal purposes as permitted under

the Library’s Acceptable Use of IT Policy.

This policy, and the staff education that accompanies it, will be reviewed in the light of lessons learned from the cyber-attack.

The files and folders copied in this way represented around 40% of the copied documents.

Thirdly, the attackers hijacked native utilities (e.g. IT tools used to administer the network) and used

them to forcibly create backup copies of 22 of the library databases, which were then subsequently

exfiltrated from the network.

It is believed that several of these databases contained some contact details of external users and customers but the library is unable to analyse exactly what data was copied in this way until some of the database infrastructure capabilities are restored.

The library does know that the customer databases compromised in this way were not full copies of the Customer Relationship Management and Single Customer View databases, but rather were extracts used for the purpose of market segmentation and the creation of email marketing lists.

As such, although they are likely to contain contact details, they are not believed to contain more sensitive details such as customer financial data.

The report is very candid in exposing not only the attack, but the failings of the Library and what will need to happen to ensure a repeat attack cannot happen.

Hopefully this report will allow others to learn from the mistakes at the British Library and will make the decision makers and purse-holders wake up and treat cyber security as a vital component of their business instead of an unnecessary expense.