(19/09/23) Blog 262 – UK achieves 7th place in MIT global Cyber Defense Index

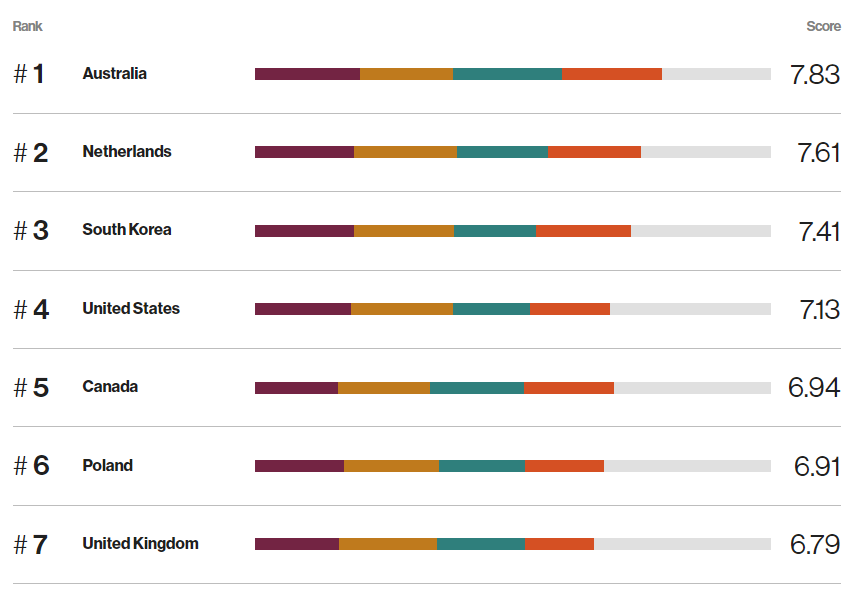

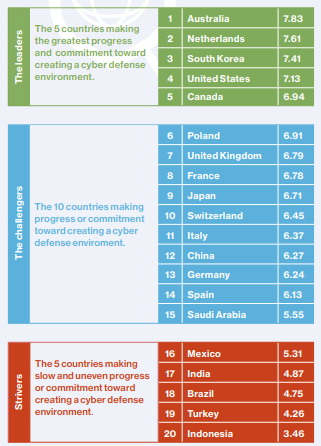

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have just released their Technology Review Insights Cyber Defense Index (CDI) for 2022/23 and has graded the UK 7th in the world at being prepared for cyber attacks, behind countries such as South Korea, Poland, and Australia.

Data sources

The research was conducted through in-depth secondary research and analysis along with primary survey data, and interviews with global cybersecurity professionals, technology developers, analysts, and policymakers.

It measures the extent to which the world’s 20 largest and most digitally forward economies have adopted technology and digital practices to resist cyber attacks, and how well their governments and policy frameworks promote cyber secure digital transactions.

The Index was developed by combining two broad sets of input data:

- Secondary source data, including global digital technology adoption statistics and policy and regulatory data, largely sourced from international institutions and benchmarks.

- A global survey of 1000 senior executives (with an equal number of respondents from each country ranked in the Index) who have cybersecurity responsibilities for their respective organizations. Forty-three percent of respondents were CIOs, CTOs, or chief security officers. Respondents were asked to rate the effectiveness of technology adoption and policy and regulation formation, and of their own cybersecurity activities, as well as to comment on their technology development priorities over the next two to three years.

The data used to inform the report came form a number of sources, including:

- United Nations E-Government Knowledgebase

- Data Center Map

- Worldometer

- Global Change Data Lab

- Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI) of the UN

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

- United Nations Conference on Trade and

Development (UNCTAD) - The World Bank Group

- Oxford Insights

The four pillars of the CDI

After collating and reviewing data, it was categorised under four pillars:

- Critical Infrastructure

This pillar indicates how well each country is served by robust and secure digital and telecommunications networks and computing resources that underpin primary economic activity. In addition to an overall indicator of telecom capacity, as assessed by the UN, these metrics incorporate the country’s number of data centers and secure servers. This pillar also includes indicators derived from our global survey in which respondents assessed the robustness of each country’s critical infrastructure. UK ranking = 9th place - Cyber security resources

This pillar collects several views of the technological and legal enforcement “assets” in each country that prevent improper access and use of data. These include the ITU’s holistic assessment of cyber security capabilities, our own ranking of digital privacy protections, and survey respondents’ views on how well cyber security tools and infrastructure are applied in their market. UK ranking = 7th place - Organisational capacity

This pillar measures the relative cybersecurity maturity and digital experience of the country’s businesses and institutions. This includes a measure of digital participation in government the extent to which organizations are familiar with artificial intelligence, and survey respondents’ assessments of the degree to which cyber security capabilities are strategic and formally integrated in their organizations. UK ranking = 6th place - Policy commitment

This pillar measures the comprehensiveness, quality, and efficacy of a country’s regulatory environment in enhancing and promoting resilient cybersecurity practices. This measure incorporates the World Bank’s evaluation of the government’s effectiveness and the quality of its cybersecurity regulation, as well as survey respondents’ assessments of the robustness and completeness of that regulation. UK ranking = 12th place

Key findings

Australia’s first-place CDI score reflects efforts to make robust digital infrastructure widely available.

The Australian government strives to use digital tools and regulations to safeguard personal data and digital transactions. It committed to overhauling cyber security laws, pledging to shelve a previous road-map. The importance of this was underscored by a hack of Optus, its second-largest mobile carrier, in which 2.8 million records were stolen. Its business leaders have high confidence in the government’s cyber security stance.

The Netherlands, in second place, is a nerve center for pan-European cyber security. The Hague is a digital security hub. It is home to the Global Forum for Cyber Expertise, and the cyber security operational headquarters for Europol and NATO. The Netherlands ranks high for cyber security resources, with comprehensive approaches to data privacy and well-coordinated domestic agencies. It benefits from the EU’s consumer friendly digital policy, reflected in the 2018 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) framework

Geopolitics means high CDI rankings for South Korea (3rd) and Poland (6th). Both economies border some of the world’s most notorious safe harbors for cyber malfeasance—Russia and North Korea—which implicitly and explicitly support bad actors. This forces increased vigilance.

China leads on several indicators (2nd place in organizational capacity), but overall ranks in the

bottom 10. China’s advantages lie in its digital workers and the strategic importance its business leaders place on cyber security. Its overall score is bruised by its poorly regarded infrastructure resilience and difficult policy environment.

Germany scored in the bottom quarter of the CDI, lowest of any EU nation. Germany has one of Europe’s

lowest e-participation scores, due to low adoption in its small-to-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), its slow digital service delivery, and its dearth of talent.

India struggles, despite a digitally forward government and the world’s largest IT-enabled service sectors.

This powerful tech force lacks critical infrastructure, has poor national digital economy adoption, and weak cyber security regulation. Despite cyber attacks and calls for cyber security laws and a dedicated ministry, India has opted out.

The EU benefits from its cyber security posture, expressed by the 2018 GDPR. This preserves the rights

of digital consumers and is a model for the top half of CDI-ranked countries. This posture affects Poland and France (6th and 8th) and the UK and Switzerland (7th and 10th), as well as non-EU European countries with large pan-European footprints in the financial service and insurance sectors.

Developing countries struggle for ground, due to lack of knowledge and resources. Countries among the

CDI top 10 score closely together—less than one point divides first-place Australia and ninth-place Japan. Those near the bottom score more diversely. The differentiator is access to investment. Cyber security advances lean on 5G technology, which requires upgrades to critical infrastructure. Where 5G is already in place, there is built-in access to innovation.