(06/05/23) Blog 126 – The royal connection to Cyber Security

Today sees the coronation of King Charles III – the 63rd monarch of England and Britain, and the 13th British monarch since the political union of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland on 1st May 1707, so I thought I’d write a suitably royal blog.

It’s also fitting that King Charles is the Royal patron of the UK Intelligence services.

Prestel

Prestel (abbrev. press telephone), was the brand name for the United Kingdom Post Office Telecommunications’s Viewdata technology and was an interactive videotex system developed during the late 1970s and was commercially launched in 1979.

Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4038944

The Prestel system was very similar in operation to that of the BBC “Ceefax” and the ITV “Teletext” systems in that the system was a database of published data pages which could be navigated by the user by entering the ID number of the page they wished to view.

So for example, the BBC Ceefax system organised data as follows:

- 100s – News

- 200s – Business News

- 300s – Sport

- 400s – Weather and Travel

- 500s – Entertainment (e.g. page 555 showed National Lottery results)

- 600s – TV and Radio Listings

The Prestel system displayed pages published by Information Providers (IPs) for the viewer to access and read.

In 1983, the Prestel messaging service known as “Prestel Mailbox” was launched, which allowed users to send messages to IPs.

In order to use the new Prestel Mailbox service, the user went to page *7# which gave the user the ability to generate “free format” messages, use pre-formatted messages and retrieve stored messages from an IP. Very similar to the email systems we all use today.

When a user messaged an IP, the system automatically added data to the message such as user’s name, address, telephone number, and date.

By late 1984 the basic Mailbox service had been extended to give automatic access to the Telex service which at the time was still relatively common in business and was the standard way to reach remoter parts of the globe.

Using a special Telex Link page, a message was composed in the usual Prestel way and then the destination country was chosen and the Telex number was entered before sending just like a standard message.

At the end of 1984 there were over 70,000 registered Prestel users, and up to 100,000 mailboxes and telexes were sent each week via Prestel Mailbox.

One of those Prestel users was HRH The Duke of Edinburgh.

Two other users were journalists Steve Gold and Robert Schifreen.

Schifreen entered the Internet hall of Infamy (if one existed!) as the first person charged with illegally accessing a computer system in 1985, after he was arrested for the unauthorised access to The Duke of Edinburgh’s Prestel Mailbox.

How did he do it?

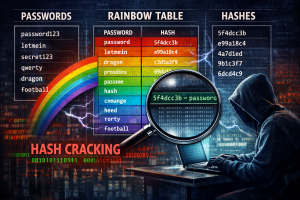

Schifreen came across a Prestel ID by shoulder surfing a BT engineer who was working on Prestel at a trade show. The ID gave him access to a BT internal Prestel page containing the phone numbers of the developer mainframes.

The ID he used was “22222222” with a password of “1234” – not a lot changes with weak credentials it appears!

After viewing the pages on the mainframe over a number of days, someone left the system manager credentials on the login page of the mainframe. This gave Schifreen full access to every Prestel mailbox on the system.

Including the Duke’s.

After he had found the manager credentials, Schifreen contacted Steve Gold (who’d been trying to also access Prestel in other ways), and then informed Micronet (Gold & Schifreen were freelance journalists working for Micronet) who informed Prestel…

…who subsequently called in the Metropolitan Police.

Unknown to Schifreen and Gold, the Prestel computer network was intended to act as a hot standby in the event of the UK going to war — in the event that the primary UK military computers were down, the Prestel network could be used to control and launch the UK’s nuclear missiles.

Following discussions with GCHQ and MI6, it was decided to investigate Schifreen and Gold’s activities.

On request from these intelligence agencies, Prestel installed monitors on both of the pair’s modem connections and, acting on the information obtained, decided it was in the best interests of national security to arrest them.

Charged

At the time of their arrests, there was no applicable law in the UK under which Gold and Schifreen could be charged, so after some months of deliberation, it was decided to charge the pair under section 1 of the Forgery and Counterfeiting Act 1981, with defrauding BT by manufacturing a “false instrument,” namely the internal condition of BT’s equipment after it had processed the eavesdropped password.

Both men were tried at Southwark Crown Court, and were convicted on specimen charges (five against Schifreen, four against Gold) and fined, respectively, £750 and £600.

Appeal

Although the fines imposed on Gold and Schifreen were modest, they elected to appeal to the Criminal Division of the Court of Appeal.

Their counsel cited a lack of evidence showing the two had attempted to obtain material gain from their exploits, and claimed the Forgery and Counterfeiting Act had been misapplied to their conduct.

They were eventually acquitted by the Lord Justice Lane, but the prosecution appealed to the House of Lords.

In 1988, the Lords upheld the acquittal.

“We have accordingly come to the conclusion that the language of the Act was not intended to apply to the situation which was shown to exist in this case. The submissions at the close of the prosecution case should have succeeded. It is a conclusion which we reach without regret. The Procrustean attempt to force these facts into the language of an Act not designed to fit them produced grave difficulties for both judge and jury which we would not wish to see repeated. The appellants’ conduct amounted in essence, as already stated, to dishonestly gaining access to the relevant Prestel data bank by a trick. That is not a criminal offence. If it is thought desirable to make it so, that is a matter for the legislature rather than the courts.”

Lord Brandon

A new law

The Gold & Schifreen case highlighted a gaping hole in UK legislation when it came to computers and IT in general.

As such it was concluded that new legislation was required.

This new legislation arrived in the form of the Computer Misuse Act (CMA) in 1990.

The CMA outlines 5 key areas of crimes associated with computers:

- Section 1 – Unauthorised access to computer material.

- Section 2 – Unauthorised access with intent to commit or facilitate commission of further offences.

- Section 3 – Unauthorised acts with intent to impair, or with recklessness as to impairing, operation of computer, etc.

- Section 3ZA – Unauthorised acts causing, or creating risk of, serious damage

- Section 3A – Making, supplying or obtaining articles for use in offence under section 1, 3 or 3ZA

And that’s the Royal connection to Cyber Security.

God Save the King…