(22/04/23) Blog 112 – OSINT pt1

We are constantly advised to be careful when posting things online as our data could be used by cyber criminals to conduct nefarious acts against us. Whilst this is very true, one thing which is often left out is how cyber criminals get our data.

This series of mini-blogs will showcase just a small set of the activities which fall under the category of Open Source Intelligence, or OSINT.

Definition of OSINT

Open-source intelligence (OSINT) is the collection and analysis of data gathered from open sources (covert sources and publicly available information [PAI]) to produce actionable intelligence. OSINT is primarily used in national security, law enforcement, and business intelligence functions and is of value to analysts who use non-sensitive intelligence in answering classified, unclassified, or proprietary intelligencerequirements across the previous intelligence disciplines

Wikipedia

OSINT is defined in the United States of America by Public Law 109-163 as cited by both the U.S. Director of National Intelligence and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), as intelligence “produced from publicly available information that is collected, exploited, and disseminated in a timely manner to an appropriate audience for the purpose of addressing a specific intelligence requirement.”

As defined by NATO, OSINT is intelligence “derived from publicly available information, as well as other unclassified information that has limited public distribution or access.”

OSINT sources can be divided up into six different categories of information flow:

- Media – print newspapers, magazines, radio, and television

- Internet – online publications, blogs, discussion groups, citizen media (i.e. – cell phone videos, and user created content), YouTube, and other social media

- Public government data – public government reports, budgets, hearings, telephone directories, press conferences, websites, and speeches.

- Professional and academic publications – information acquired from journals, conferences, symposia, academic papers, dissertations, and theses

- Commercial data – commercial imagery, financial and industrial assessments, and databases

- Grey literature – technical reports, preprints, patents, working papers, business documents, unpublished works, and newsletters

OSINT is distinguished from research in that it applies the process of intelligence to create tailored knowledge supportive of a specific decision by a specific individual or group

The start of an attack

When cyber criminals target a company, they will begin their attack by conducting OSINT on that company, it’s staff, its customers, its suppliers, and more.

By building up a picture of the organisation, criminals will be able to hone their attack tools in preparation for the attack – be that by targeting a weakness in their security systems (hacking), a weakness in their staff (social engineering), or a weakness in their suppliers (supply chain attack), or some other avenue of attack.

Good OSINT is vital when conducting a social engineering attack – attackers need to know names, places, dates, corporate lingo (buzz words, acronyms, project titles, etc.) to come across as legitimate and trustworthy.

In this series of blogs I will look at various aspects of conducting OSINT against various targets.

The company profile

To begin with, the most simplistic approach to conducting an OSINT operation against an organisation is to visit their website.

Company websites can offer a huge amount of useful information – below are some examples of what a corporate website could offer.

If the website has a “meet the staff” page, or similar – This will uncover a raft of information about key staff members – Who the C-suite members* are and other key staff members.

*C-Suite is a term used to identify those executive members who’s titles typically begin with a C – i.e. CEO (Chief Executive Officer), CTO (Chief Technical Officer), CFO (Chief Finance Officer), etc.

If the website features a “news” page, you may get useful information about project titles, or work recently undertaken by the company which might give you a level of credence if engaging in a conversation with a staff member.

Explore the site looking for any email addresses – any that directly mention staff names could be useful, but more so the structure of email addresses at the company – i.e. firstname.surname@company.com or surname.initial@company.com, etc. By knowing the email structure, you have the ability to spam various possible email addresses in a phishing campaign.

Look to see if the site has any files which could be downloaded – files like this can contain useful metadata (more on this in a later post).

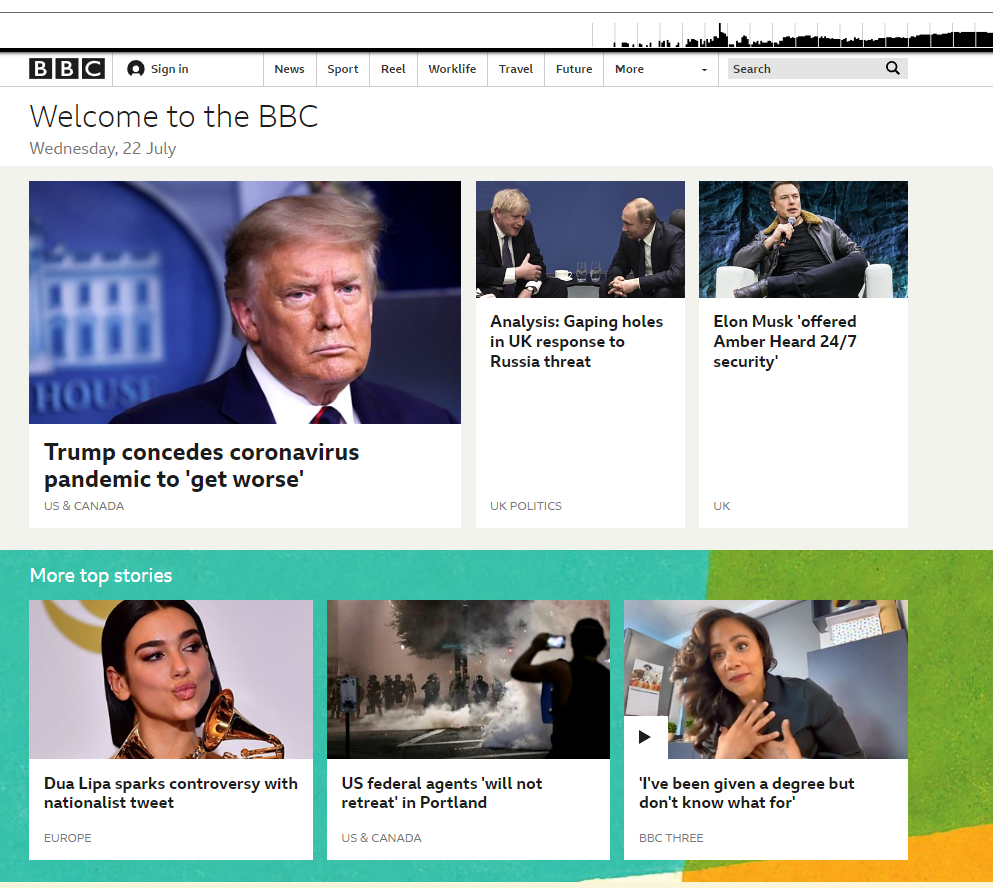

A useful thing to do is to explore old versions of the website – companies today are more aware of security issues, such as the ones I’m mentioning here, and may have taken steps to limit the amount of sensitive data they now post on their websites.

Old versions of the site might not have been so security conscious, and may offer a lot of useful data.

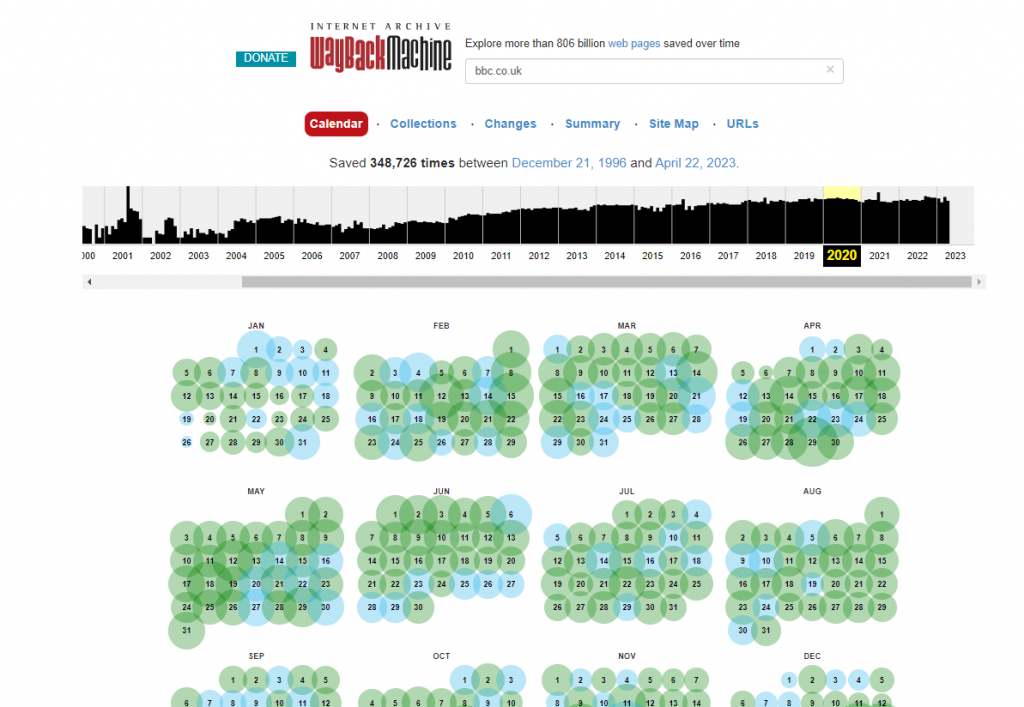

The wayback machine is a fantastic resource for exploring old versions of websites.

When using the wayback machine, you enter the web address of the site you wish to explore, then pick a year from the timeline at the top of the page. From the calendar below, select one of the coloured circles and then pick a date to extract the archive data.

Behind the scenes

As well as looking at the websites as it is intended to be viewed, there are other avenues to explore with regards to the site’s structure.

Robots & sitemaps

When people build websites, they ideally want to ensure they get as much visibility as possible – and that means making sure search engines can index the site efficiently.

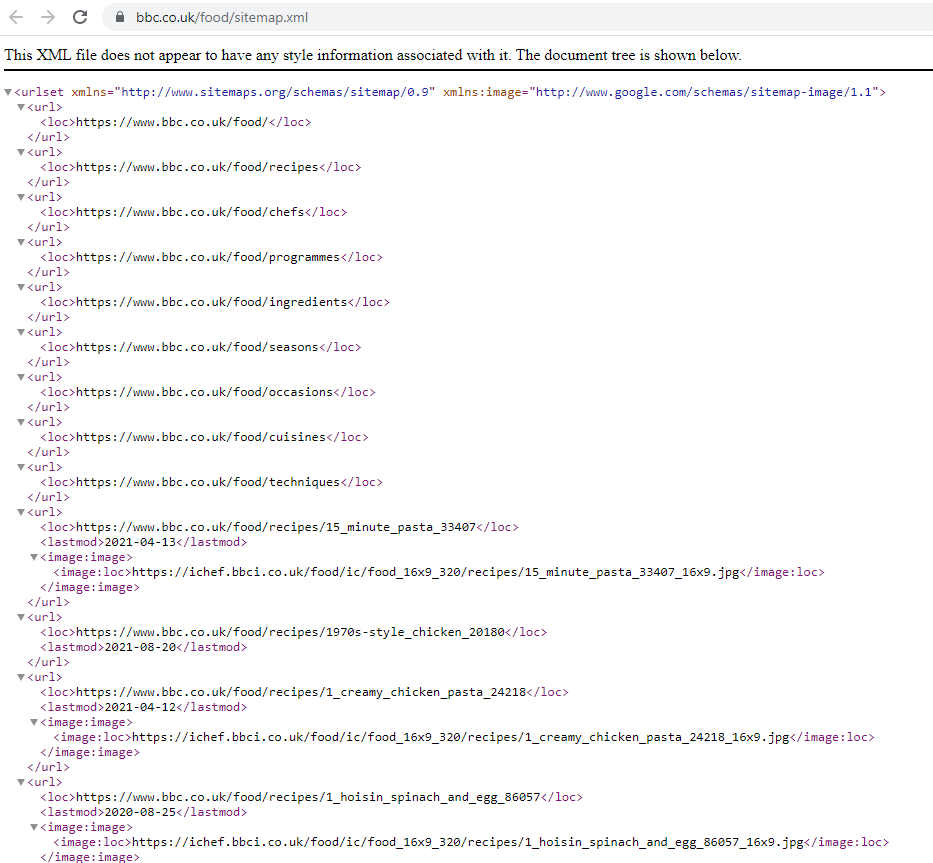

To assist in this process, two specific files are used to help search engines: – robots.txt & sitemap.xml

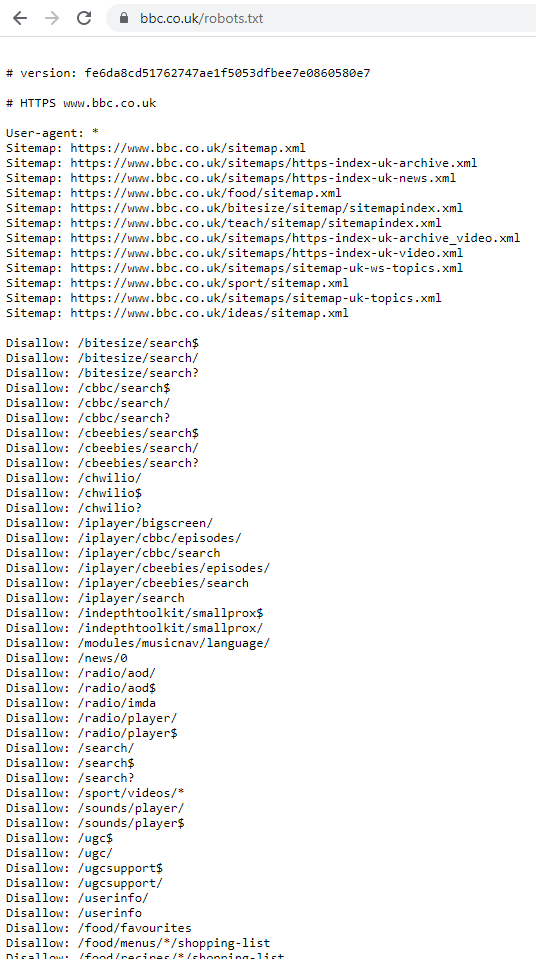

The robots.txt file is a simple text file located at the root of a website which instructs search engine spiders (aka robots) which folders and files they are not supposed to index.

A typical robots.txt file would look something like the one shown below:

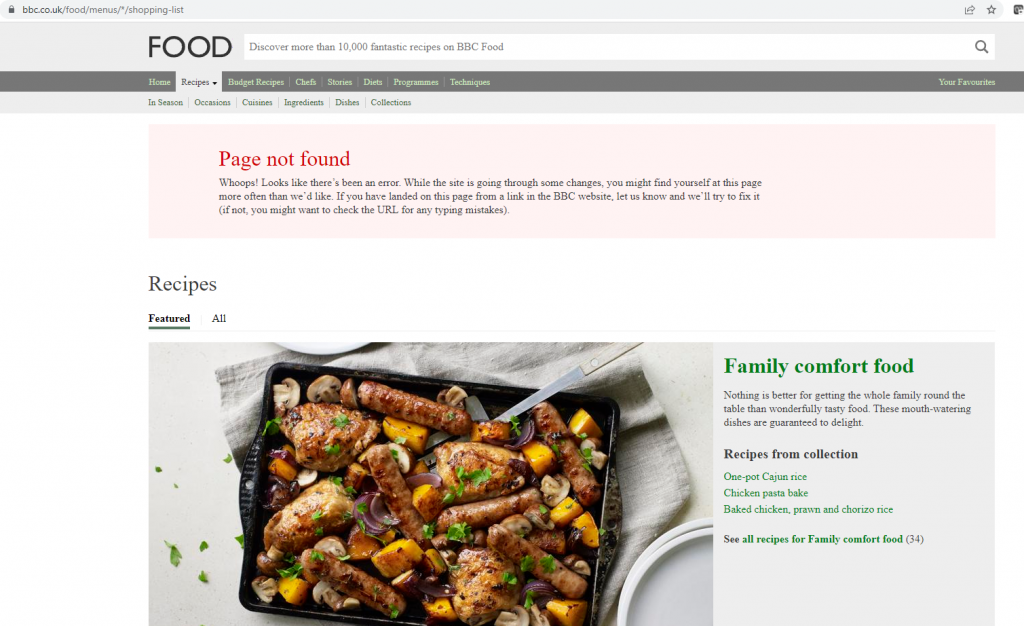

As you can see from the image, the bbc has a robots.txt file which includes not only a list of sitemap.xml files, but also a series of disallow URLs.

The purpose of the disallow URLs is to inform a search engine which folders they should not index. However – this does not stop a human from manually navigating to the same files & folders.

The sitemap.xml file holds a list of all the URLs which a website wants a search engine to index – again, a useful list for an OSINT investigation.

Whilst browsing a site manually can return some good results, it will be a very time-consuming and laborious process. As such, automated tools exist which will do the work for you.

There are many tools available (free and paid-for) which will swiftly navigate through a website and highlight any useful data. One such tool is browse.ai which, as the name suggests is an Artificial Intelligence utility dedicated to browsing websites.

Another tool which requires a bit more knowledge of websites is the Linux wget utility which can retrieve all manner of content from websites – it can even be used to clone entire sites for local hosting and exploration.

SourceCode

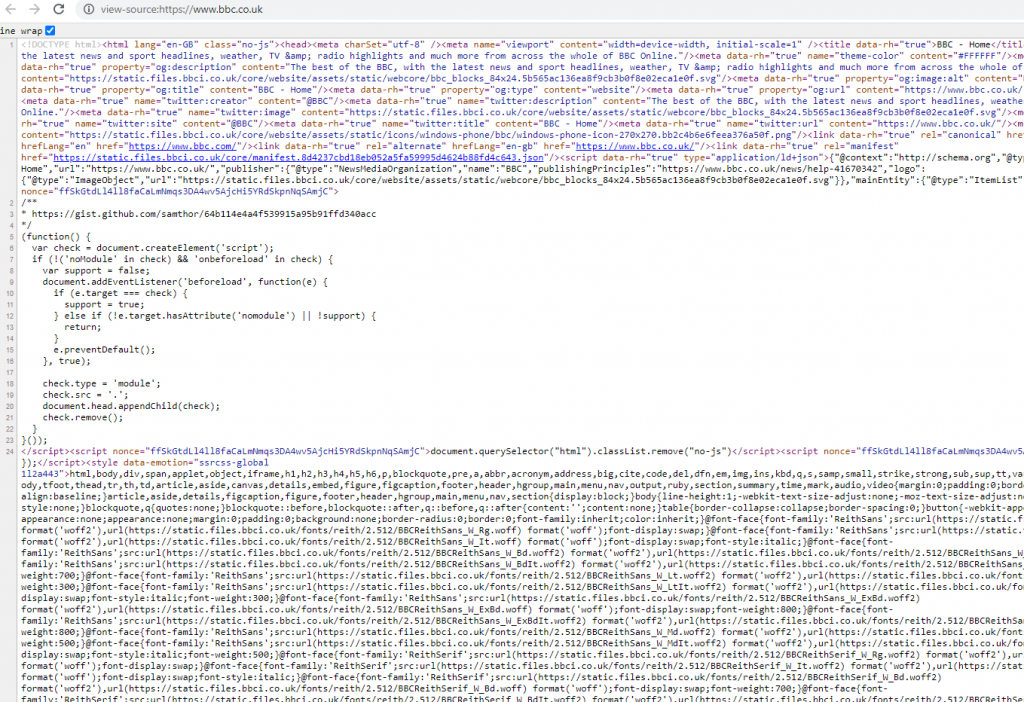

All websites and webpages are constructed using HTML. When viewing a webpage, it is sometimes useful to view the underlying HTML to see if there are any snippets of code left behind by developers that could be useful.

When viewing a webpage, you can right-click the page and select the option to view the sourcecode – this will display a new tab in the browser with the HTML of the webpage you are viewing – comments are useful things to go looking for.

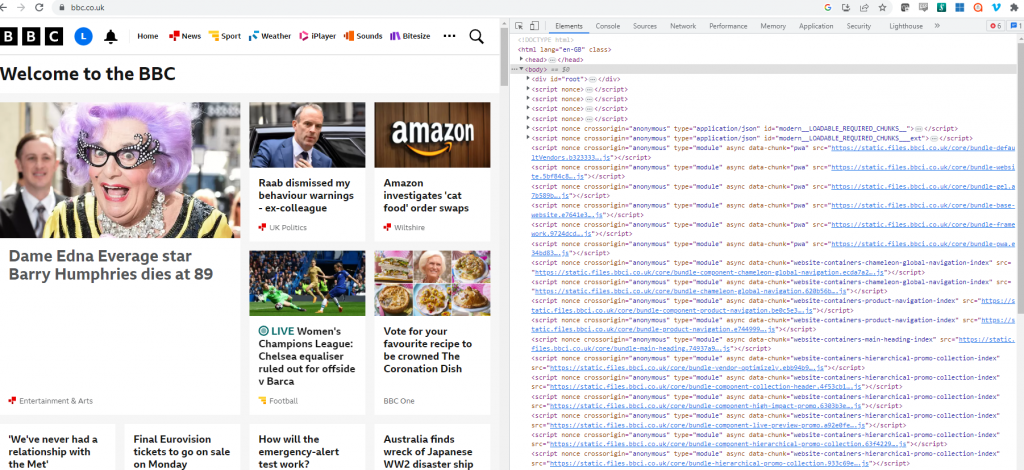

As an alternative to viewing the sourcecode, you might opt for using the developer tools in your browser – by pressing F12, a new panel will open in your browser that shows the sourcecode of the webpage, but a whole set of tools an utilities which you can use to explore the website you are investigating.

Building blocks

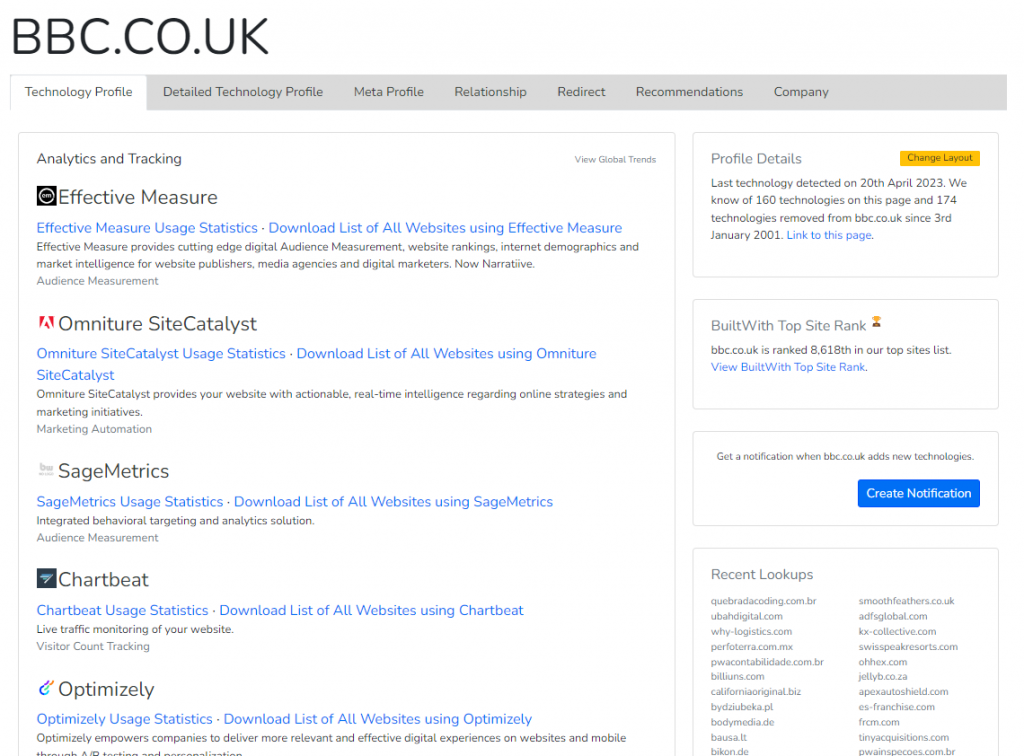

Another useful activity to conduct when looking at a corporate website is to identify the various technologies used to actually construct the site.

The website Builtwith.com is a great resource that will list all the various technologies a website uses.

A wider view

Once the main corporate website has been explored for any useful data, it is advisable to see if there are any other domains, or sub domains owned by the target company which might also offer useful data.

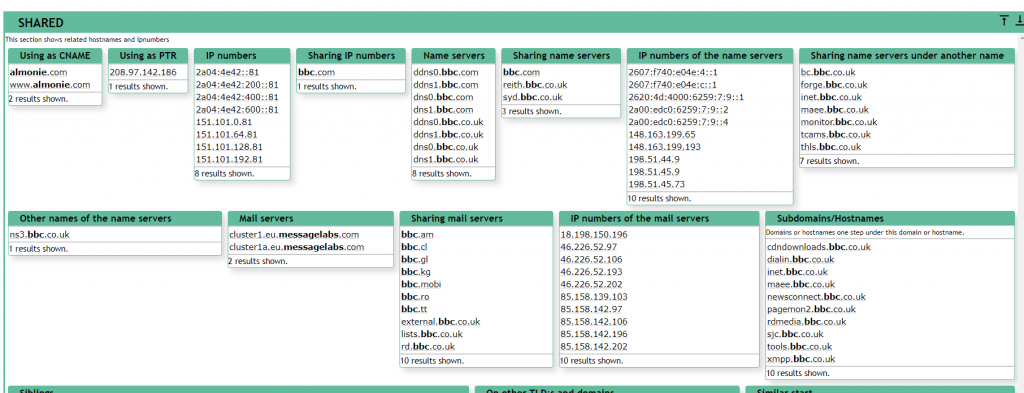

One of the most widely used sites for this type of OSINT is robtex.com, which is an online utility which automates the processes of domain enumeration and can identify all manner of data associated with specified domain.

Information such as email servers, DNS name servers, sub-domains, Autonomous Systems (AS) and more can be quickly obtained via this website.

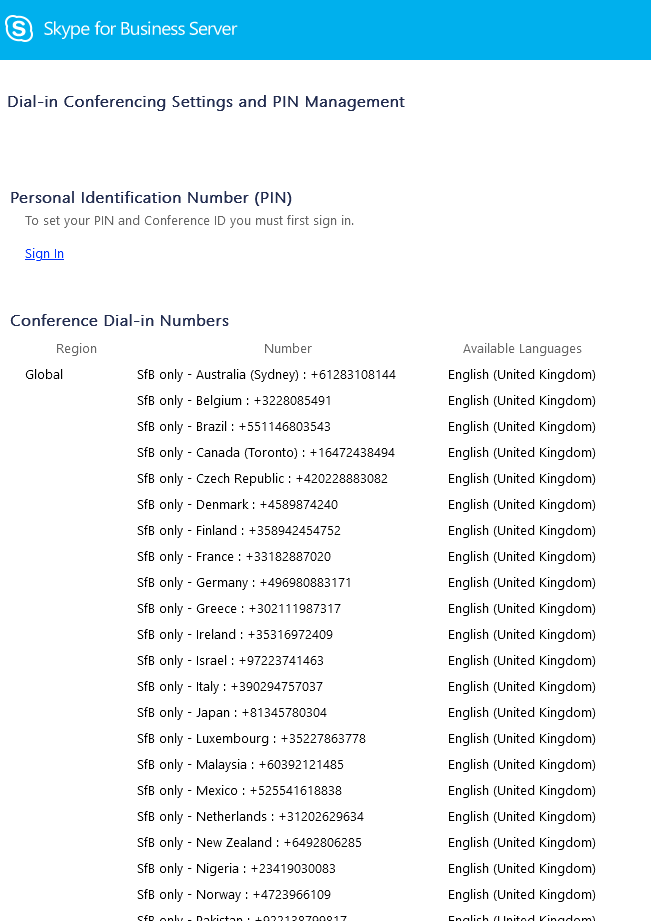

In the above search, a URL dialin.bbc.co.uk is identified – this URL holds a list of Skype telephone numbers for people to use when communicating with the BBC. This could be useful to a would-be attacker / social engineer.

Industry websites

After thoroughly exploring the corporate website, it is worth also looking at related websites for companies in the same industry.

For example, if your target company is in the construction industry, then there are multiple other sites dedicated to news about the world of construction – some of them might give you other useful data about your target company – tenders won, projects undergoing, new hires, awards given, etc.

In my next post, I will take a look at other ways to identify possible subjects of interest in an OSINT investigation by looking at social media.